Cryptographic vulnerabilities are considered so spooky that often, seasoned vulnerability researchers and exploit developers don’t even bother searching for them. But the truth is, many cryptographic vulnerabilities require very little mathematics. It’s more-often the case that something has been misconfigured, nonces have been re-used, cryptographic primitives have been misused, or nonces have been re-used. (See what I did there?).

In this post I’m going to take a very quick look at a class of attacks that exist against hash functions belonging to the Merkle-Damgård family, and explain why Keccak256 is not vulnerable to such attacks.

Merkle-Damgård

First of all - what are Merkle-Damgård hashes? Broadly, they are any hashing algorithm which uses a Merkle-Damgard construction under the hood.

Examples of Merkle-Damgård hashes include:

- SHA-1

- SHA-2

- MD5

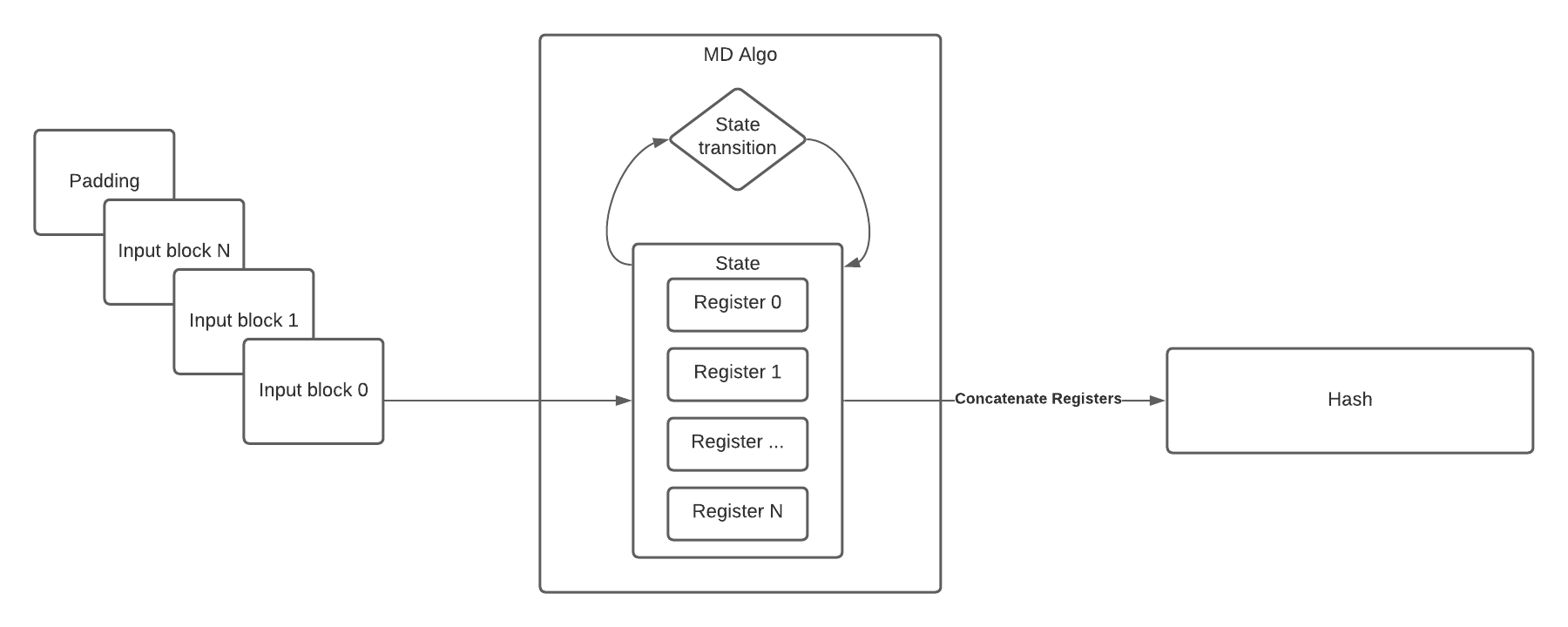

Merkle-Damgård (MD, henceforth) hashing algorithms can be visualized as a collection of register-states, along with a function which transitions those states into a new set of register states, like so:

Looking at the above diagram, there are two important things of note.

- The internal state of the algorithm is made up of some number of registers.

- That number differs from MD hash to MD hash.

- The output of the function is the concatenation of those internal registers in their entirety.

- Only true of certain length hashes, like SHA-256 and SHA-512.

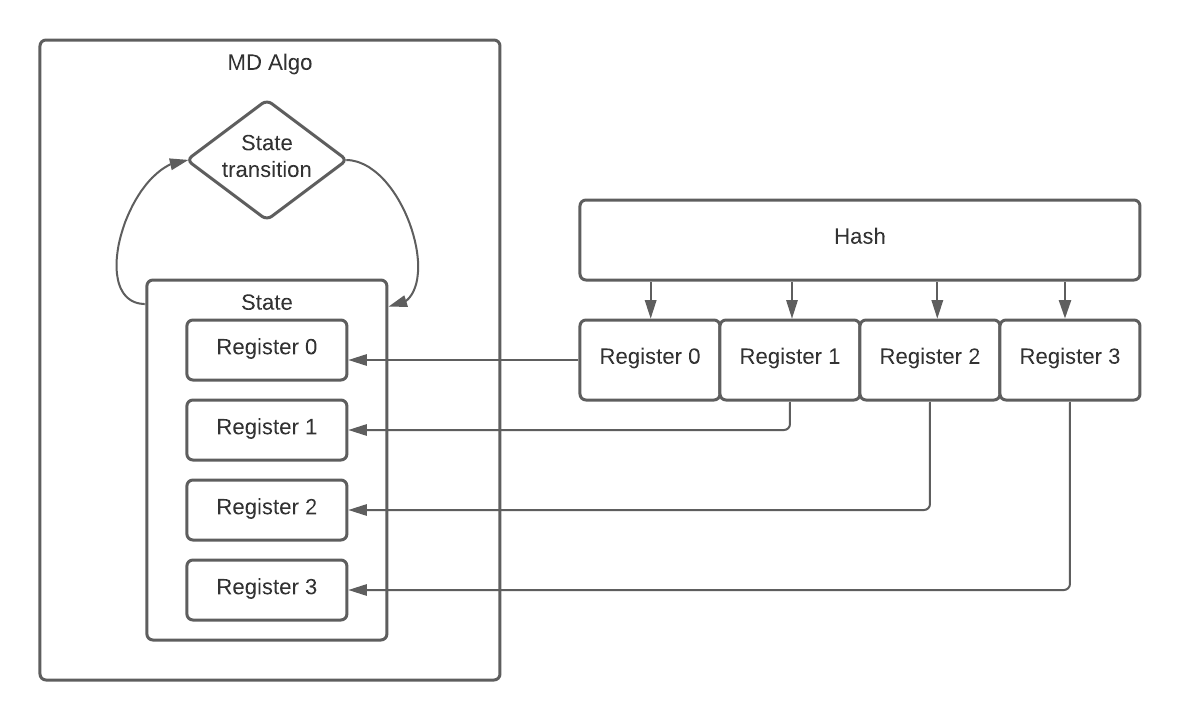

Given this information, it’s clear that we can re-create the internal state of the hashing algorithm from the hash itself, like so:

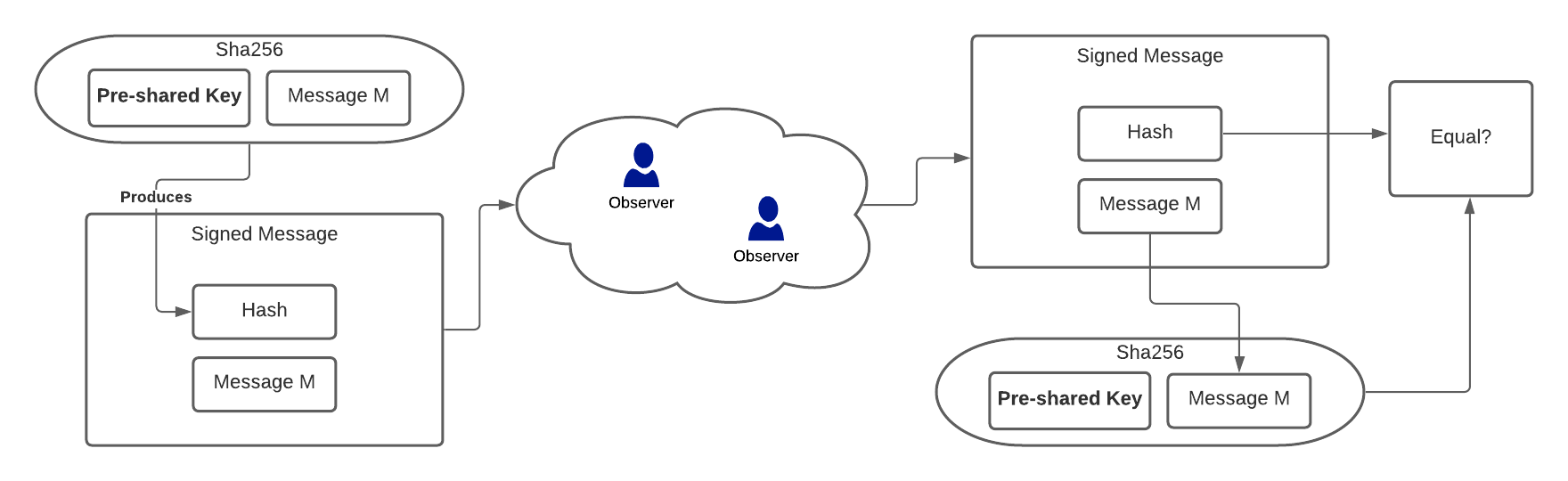

If we can re-create the internal state of the hashing algorithm, we can pickup right where we left off. This is the crux of hash length extension attacks. For this reason, patterns like the following are dangerous:

Because an attacker who intercepts and forwards the message doesn’t need to know the pre-shared-key in order to append data to the message. This pattern of message signing was exploited in 2009 to break the Flickr API. It’s a great case-study, because the cryptographic primitives worked exactly as intended, they were just used in a way that didn’t provide the protection the developer thought they were getting.

This GitHub repo, which borrows heavily from this gist, demonstrates an MD length extension attack. The hash is manually loaded into the registers of the hashing algorithm’s state, and more text is appended to the hash, which is then forwarded along with the original message. No complicated mathematics required. The only caveat is that the length of the pre-shared-key needs to be known in order to forge the signature - but it’s usually trivially brute-forcable, as demonstrated in the repo.

So how is Keccak256 resistant to this kind of attack?

Keccak256

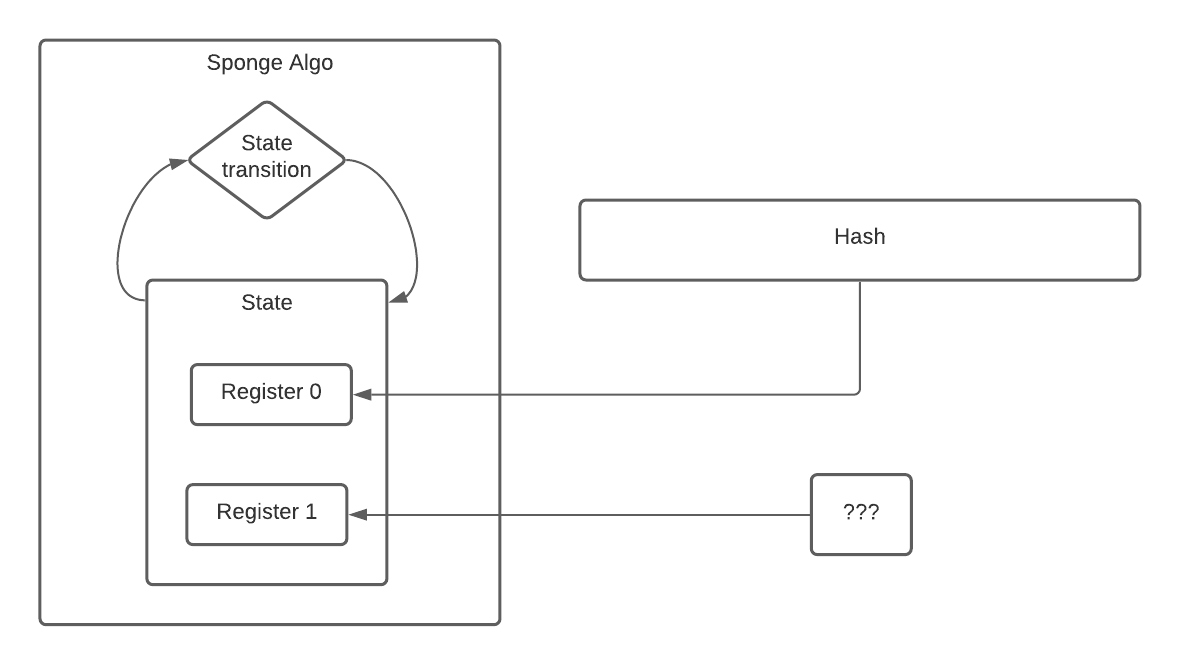

The thing which made our MD family of hashes vulnerable was the fact that the internal state of the algorithm can be re-created from the attacker observable output. As you may have guessed, this is not the case with Keccak256.

Instead of a MD construction, Keccak256 uses what’s called a Sponge function. The sponge function breaks its internal state into multiple parts, and produces the output hash from only one of these parts during what is called the “squeezing” phase of the algorithm. By only capturing a small part of the internal state in the output hash - it’s made extremely difficult (infeasible) to re-create the algorithm’s internal state and append new data to the hash:

Note that I’m using 2 registers to represent some known state and some unknown state; real sponge algorithms (like Keccak) may use more.

At a very high-level, that’s one of the ways Keccak’s sponge construction differs from previous MD construction, and how it mitigates hash length extension.