Once a smart contract is published - its code cannot change. It is immutable - and will behave exactly as it has been coded to behave. There is no room for ambiguity in the interpretation.

This is one of the innovations we get with smart-contracts executing upon distributed virtual machines - like Ethereum.

There are still assumptions to be made, the principal one being that the Ethereum Network behaves as expected. There’s risk associated with this assumption - but by encouraging network participants to behave in a way that keeps the network behaving as we’d expect (by exploiting branches of mathematics like game-theory), we can encourage rational behaviour.

Immutability and disambiguation are important in contracts of all sorts - but the truth is, things change.

There’s a trade-off to be made here - are there cases where we might trade that immutability for flexibility? I’d argue yes in many cases. Parties involved in a contract may mutually agree upon some change, unexpected events in our environment might necessitate a change. Mistakes in the way the contract was written might necessitate a change.

So how do we reconcile this need for flexibility with the immutability of the blockchain?

The answer is with upgradable proxy patterns. But first, let’s look at a typical immutable contract.

A Typical Contract

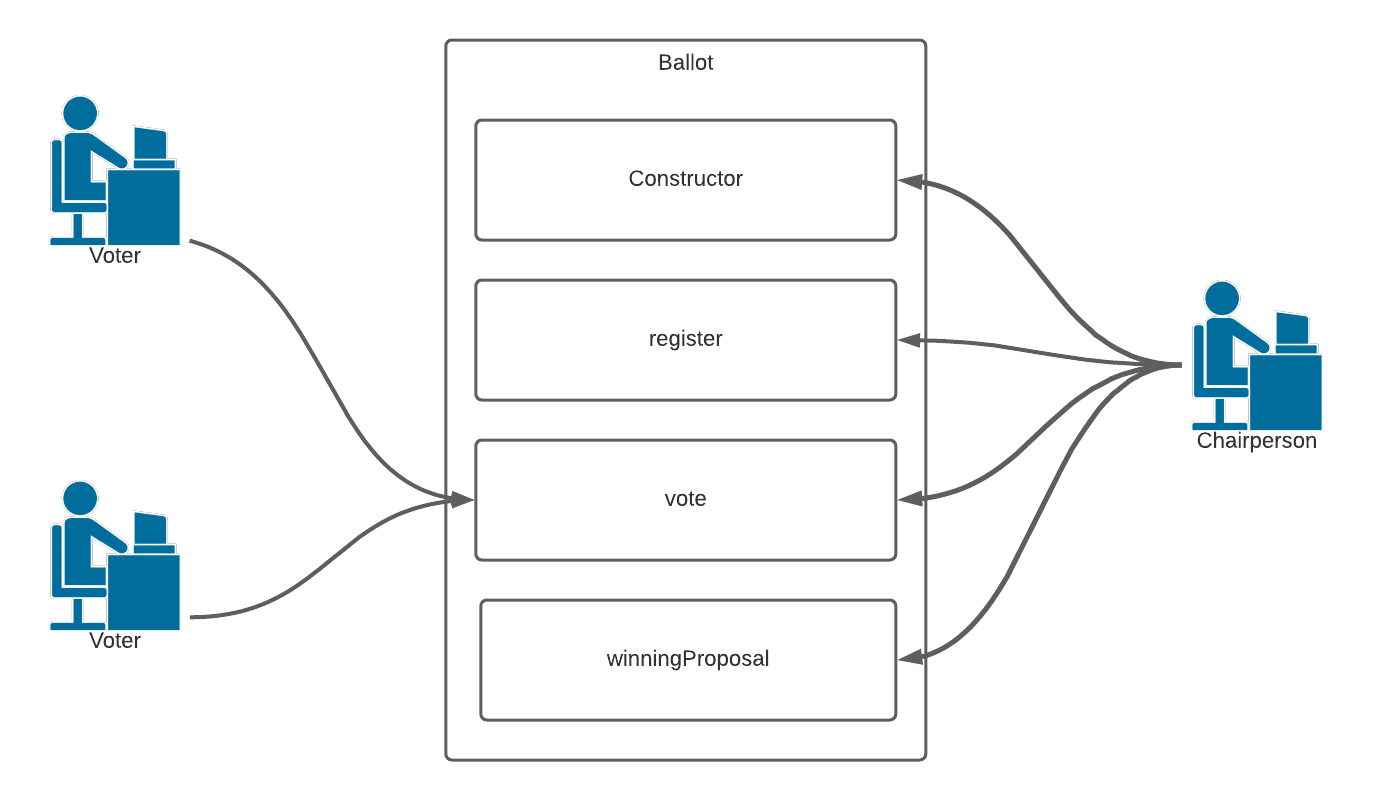

Here’s a typical, immutable contract who’s purpose is to facilitate some chairperson initiating a ballot, voters registering, everyone casting their vote, and recording the winning option:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Ballot {

struct Voter {

uint weight;

bool voted;

uint8 vote;

//address delegate;

}

struct Proposal {

uint voteCount;

}

enum Stage {Init,Reg, Vote, Done}

Stage public stage = Stage.Init;

address chairperson;

mapping(address => Voter) voters;

Proposal[] proposals;

event votingCompleted();

uint startTime;

//modifiers

modifier validStage(Stage reqStage)

{ require(stage == reqStage);

_;

}

modifier onlyBy(address _account)

{

require(msg.sender == _account);

_;

}

/// Create a new ballot with $(_numProposals) different proposals.

constructor(uint8 _numProposals) {

chairperson = msg.sender;

voters[chairperson].weight = 2;

for(uint i = 0; i < _numProposals; i++){

//new syntax since length is not writable

proposals.push();

}

stage = Stage.Reg;

startTime = block.timestamp;

}

/// Give $(toVoter) the right to vote on this ballot.

/// May only be called by $(chairperson).

function register(address toVoter) public validStage(Stage.Reg) onlyBy(chairperson) {

if (msg.sender != chairperson || voters[toVoter].voted) return;

voters[toVoter].weight = 1;

voters[toVoter].voted = false;

if (block.timestamp > (startTime+ 30 seconds)) {stage = Stage.Vote; }

}

/// Give a single vote to proposal $(toProposal).

function vote(uint8 toProposal) public validStage(Stage.Vote) {

Voter storage sender = voters[msg.sender];

if (sender.voted || toProposal >= proposals.length) return;

sender.voted = true;

sender.vote = toProposal;

proposals[toProposal].voteCount += sender.weight;

if (block.timestamp > (startTime+ 60 seconds)) {stage = Stage.Done; emit votingCompleted();}

}

function winningProposal() public validStage(Stage.Done) view returns (uint8 _winningProposal) {

uint256 winningVoteCount = 0;

for (uint8 prop = 0; prop < proposals.length; prop++) {

if (proposals[prop].voteCount > winningVoteCount) {

winningVoteCount = proposals[prop].voteCount;

_winningProposal = prop;

}

}

assert (winningVoteCount > 0);

}

}

This is one of the sample contracts from Remix, with a couple of modifications.

It’s made some questionable design decisions, such as the logic to progress the stage state, but we won’t worry about those in this post.

The API is pretty simple, we have:

-

constructor(uint8 _numProposals)

-

function register(address toVoter) public validStage(Stage.Reg) onlyBy(chairperson)

-

function vote(uint8 toProposal) public validStage(Stage.Vote)

-

function winningProposal() public validStage(Stage.Done) view returns (uint8 _winningProposal)

And the client interaction might look like this:

An EOA (Externally Owned Address) will send a transaction to a smart contract address, indicating which function it wants to call in the transaction’s msg.data field.

The smart contract’s code is executed, and it updates whatever state it wants.

In this example, the client can be entirely sure what code will be executed and what it will do. It is an immutable contract at a specific address.

But what if disaster strikes, and all of a sudden, vast swathes of humanity lose access to the Ethereum network, perhaps through some unexpected act of nature?

It would be reasonable for the chairperson to want to extend the voting period - but they can’t. This contract’s logic is fixed on the blockchain, and much of humanity will never get their chance to influence this vote.

This is an (albeit a somewhat contrived) example of where upgrading the logic of a smart contract might be desirable.

Proxy Contracts

A “Proxy contract” is an abstract term for a contract which forwards some functionality on to another contract.

We’re going to refactor our Ballot contract to use a proxy-contract, and we’re going to learn why proxies look the way they do in the process.

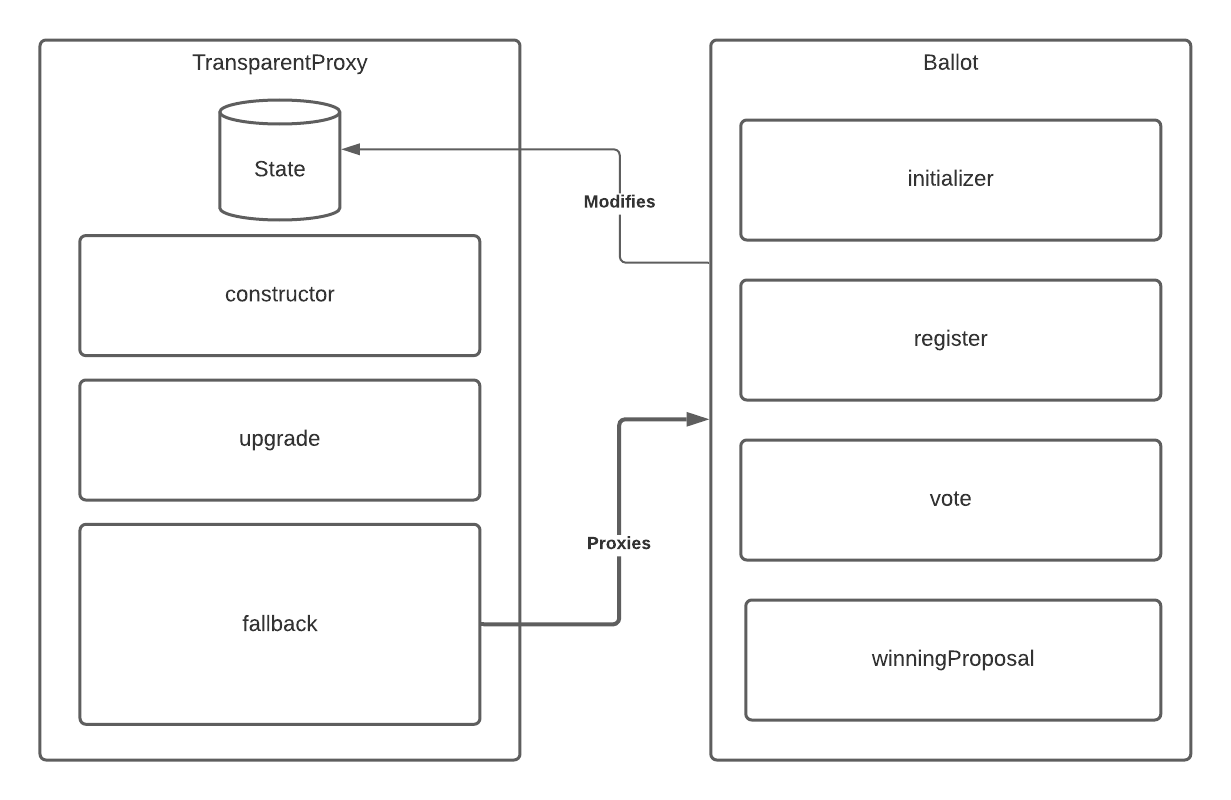

We’re going to consider the following architecture:

Here we have a proxy contract that acts as the interface to our ballot contract. The variable used as the address to the ballot contract is just that - it’s variable. The proxy contract itself acts as our storage; the reason for this will become apparent shortly.

All of a sudden, we’ve introduced mutable logic to our immutable infrastructure - we can change the address of the implementation contract which is referenced by the proxy contract.

This looks great at first, but as mentioned - we’ve actually invalidated one of the innovations we highlighted earlier. The logic of our contract can now be subject to change. There are strategies which try and mitigate the counterparty risk in this case, such as time-locks, but the truth is that there’s rarely a free lunch, and we have indeed lost the promise of immutability.

There are a variety of architectures which can solve this problem - of differing complexity to meet a requirement of needs. OpenZeppelin provides a detailed comparison of the ones they offer here. Any production contract should use a production quality proxy contract, such as one of the ones offered by OpenZeppelin. To keep this post short - I’m going to propose a very simple contract which will demonstrate the key ideas.

So we now have a pair of contracts - one which contains our business logic, and one which contains our storage (or our ‘state’). How might the logic contract go about using the state in the proxy contract?

To answer that question, we’re going to have to understand the delegatecall functionality offered by solidity, and how storage slots work.

Delegatecall

delegatecall is an EVM instruction (and built-in function) which allows one contract to call a function in another, whilst maintaining its own context as the execution context. For traditional Object-Oriented programmers - this is not dissimilar to calling a static function, passing in your own 'this' pointer.

There’s a slight problem with the delegatecall built-in versus the delegatecall instruction.

- The built-in returns a bool, which indicates whether or not the call was successful.

- This makes it tricky to propagate return codes from the function being called.

- With some in-line assembly, we can use the

delegatecallinstruction to perform the same functionality as the built-in, but return the actual return value of the function, like so (example taken from OpenZeppelin)

assembly {

// (1) copy incoming call data

calldatacopy(0, 0, calldatasize())

// (2) forward call to logic contract

let result := delegatecall(gas(), implementation, 0, calldatasize(), 0, 0)

// (3) retrieve return data

returndatacopy(0, 0, returndatasize())

// (4) forward return data back to caller

switch result

case 0 { revert(0, returndatasize()) }

default { return(0, returndatasize()) }

}

By placing this assembly in the proxy contract’s fallback function - any function which a client calls on the proxy contract which the proxy contract does not have will be transparently forwarded to the configurable logic contract. This way we can change the API of our logic contract without having to change the proxy contract at all. Furthermore, we can upgrade the logic of the contract without losing all of the state we’ve gathered so far, because the state our logic operates on will be bound to the proxy contract.

There’s a caveat with this model which I alluded to in the previous section - our logic contract must define its variables in the same way as the transparent proxy has.

This has to do with the way the EVM stores and retrieves variables, and solving it requires some lower-level knowledge of the EVM.

EVM Storage Slots

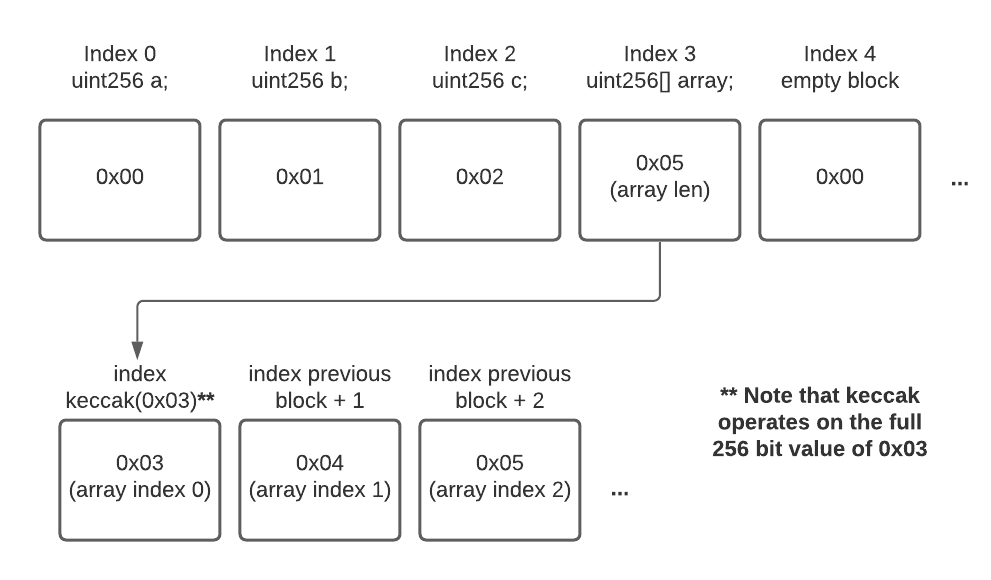

The EVM stores statically sized variables in ‘slots’ starting at index 0, the code provided below stores its data in a fashion represented by the accompanying image:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract StorageExample {

uint256 public a;

uint256 public b;

uint256 public c;

uint256[] public array;

constructor(uint256 _a, uint256 _b, uint256 _c, uint[] memory _array) {

a = _a;

b = _b;

c = _c;

array = _array;

}

}

The slot referenced by array stores the length of the array, and the slot of index 0 of the underlying storage is found by taking a keccak hash of this index - which is 0x03, zero padded to 256 bits.

This contract is actually deployed to 0x1c5D2f299d360EEDD83CFb33a19530adD06123ef on Ropsten, so you can try it yourself in a browser with metamask installed:

await ethereum.enable()

//dump the indexes 0 through 3

for(let i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

ethereum.request(

{

method: 'eth_getStorageAt',

params: [

"0x1c5D2f299d360EEDD83CFb33a19530adD06123ef",

"0x" + i.toString(16),

"latest"

]

}

).then((x) => console.log("Storage slot: " + i + " " + x))

}

//get the slot of the first array element

//keccak256(0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000003)

// =

//0xc2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85b

//get the first array element

ethereum.request(

{

method: 'eth_getStorageAt',

params: [

"0x1c5D2f299d360EEDD83CFb33a19530adD06123ef",

"c2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85b",

"latest"

]

}

).then((x) => console.log("First array element is: " + x))

// output, order may differ due to asynchronicity

//Storage slot: 1 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

//Storage slot: 2 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000002

//Storage slot: 0 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

//Storage slot: 3 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000005

//First array element is: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000003

Things get tricky when we use delegatecall.

How does the callee contract which has been called know what is stored at the various slots in the caller contract? The truth is, it doesn’t.

When a contract which is going to be a callee of a delegatecall is written, it needs to be told what to expect in which slots. What this means is that if our proxy defines its storage variables like so:

uint256 public a;

uint256 public b;

uint256 public c;

uint256[] public array;

The callee must also define its variables in the same order, which will allow it to grab the correct underlying storage slot at EVM level.

There are some extra steps we can take to protect our proxy contract’s slots from being mistreated - these steps are defined in EIP-1967. If you’re dealing with proxy contracts, you really must read EIP-1967. It defines a way of storing important contract variables in such a way that it’s very unlikely for a target contract to mistakenly overwrite those important variables by making it highly unlikely their slots with ever clash with another variable’s.

Another final difference is to do with constructors. A constructor’s code is never actually published to the blockchain - it’s only executed when the contract is deployed. What this means is there’s no way for our proxy to ever call a constructor function, it simply isn’t there. Common practice is to re-factor the constructor logic into an initialization function, which can be called instead.

Taking all of this into account, let’s take a look at our ballot contracts now:

//TransparentProxy.sol

//"SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED"

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract TransparentProxy {

struct Voter {

uint weight;

bool voted;

uint8 vote;

}

struct Proposal {

uint voteCount;

}

enum Stage {Init,Reg, Vote, Done}

//Variables, defined in exactly the same way as in the logic contract.

Stage public stage = Stage.Init;

address chairperson;

mapping(address => Voter) voters;

Proposal[] proposals;

Voter sender;

uint startTime;

//End variables

//Constants don't use storage slots

bytes32 internal constant _IMPLEMENTATION_SLOT = 0x360894a13ba1a3210667c828492db98dca3e2076cc3735a920a3ca505d382bbc;

bytes32 internal constant _ADMIN_SLOT = 0xb53127684a568b3173ae13b9f8a6016e243e63b6e8ee1178d6a717850b5d6103;

struct _addressSlot {

address value;

}

//isOwner modifier, prevents anyone other than owner from upgrading contract implementation

modifier isOwner() {

require(msg.sender == getAddressSlot(_ADMIN_SLOT).value);

_;

}

//Constructor, sets admin slot to msg.sender

constructor(address _implementation){

getAddressSlot(_ADMIN_SLOT).value = msg.sender;

upgradeLogic(_implementation);

}

//get an address from a slot

function getAddressSlot(bytes32 slot) internal pure returns (_addressSlot storage r) {

assembly {

r.slot := slot

}

}

//overwrite the implementation slot, isOwner only.

function upgradeLogic(address _newImplementation) isOwner public {

getAddressSlot(_IMPLEMENTATION_SLOT).value = _newImplementation;

}

fallback() external {

address implementation = getAddressSlot(_IMPLEMENTATION_SLOT).value;

assembly {

calldatacopy(0, 0, calldatasize())

let result := delegatecall(gas(), implementation, 0, calldatasize(), 0, 0)

returndatacopy(0, 0, returndatasize())

switch result

case 0 { revert(0, returndatasize()) }

default { return(0, returndatasize()) }

}

}

}

And:

//Ballot.sol

//"SPDX-License-Identifier: UNLICENSED"

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Ballot {

struct Voter {

uint weight;

bool voted;

uint8 vote;

//address delegate;

}

struct Proposal {

uint voteCount;

}

enum Stage {Init,Reg, Vote, Done}

//Variables, defined in exactly the same way as in the logic contract.

Stage public stage = Stage.Init;

address chairperson;

mapping(address => Voter) voters;

Proposal[] proposals;

Voter sender;

uint startTime;

//End variables

event votingCompleted();

//modifiers

modifier validStage(Stage reqStage)

{ require(stage == reqStage, "Wrong stage");

_;

}

modifier onlyBy(address _account)

{

require(msg.sender == _account, "Only chairperson can register voters");

_;

}

/// Create a new ballot with $(_numProposals) different proposals.

constructor() {

}

/// Create a new ballot with $(_numProposals) different proposals.

function initialize(uint8 _numProposals) public {

require(chairperson == address(0x0), "Cannot re-initialize contract"); //prevent re-initialization

chairperson = msg.sender;

voters[chairperson].weight = 2;

for(uint i = 0; i < _numProposals; i++){

//new syntax since length is not writable

proposals.push();

}

stage = Stage.Reg;

startTime = block.timestamp;

}

/// Give $(toVoter) the right to vote on this ballot.

/// May only be called by $(chairperson).

function register(address toVoter) public validStage(Stage.Reg) onlyBy(chairperson) {

if (msg.sender != chairperson || voters[toVoter].voted) return;

voters[toVoter].weight = 1;

voters[toVoter].voted = false;

if (block.timestamp > (startTime+ 30 seconds)) {

stage = Stage.Vote;

startTime = block.timestamp;

}

}

/// Give a single vote to proposal $(toProposal).

function vote(uint8 toProposal) public validStage(Stage.Vote) {

sender = voters[msg.sender];

require(!sender.voted, "Can't vote twice");

require(toProposal < proposals.length, "Can't vote twice");

require(sender.weight > 0, "Only registered voters can vote");

sender.voted = true;

sender.vote = toProposal;

proposals[toProposal].voteCount += sender.weight;

if (block.timestamp > (startTime+ 30 seconds)) {

stage = Stage.Done;

startTime = block.timestamp;

emit votingCompleted();

}

}

function winningProposal() public validStage(Stage.Done) view returns (uint8 _winningProposal) {

uint256 winningVoteCount = 0;

for (uint8 prop = 0; prop < proposals.length; prop++) {

if (proposals[prop].voteCount > winningVoteCount) {

winningVoteCount = proposals[prop].voteCount;

_winningProposal = prop;

}

}

assert (winningVoteCount > 0);

}

}

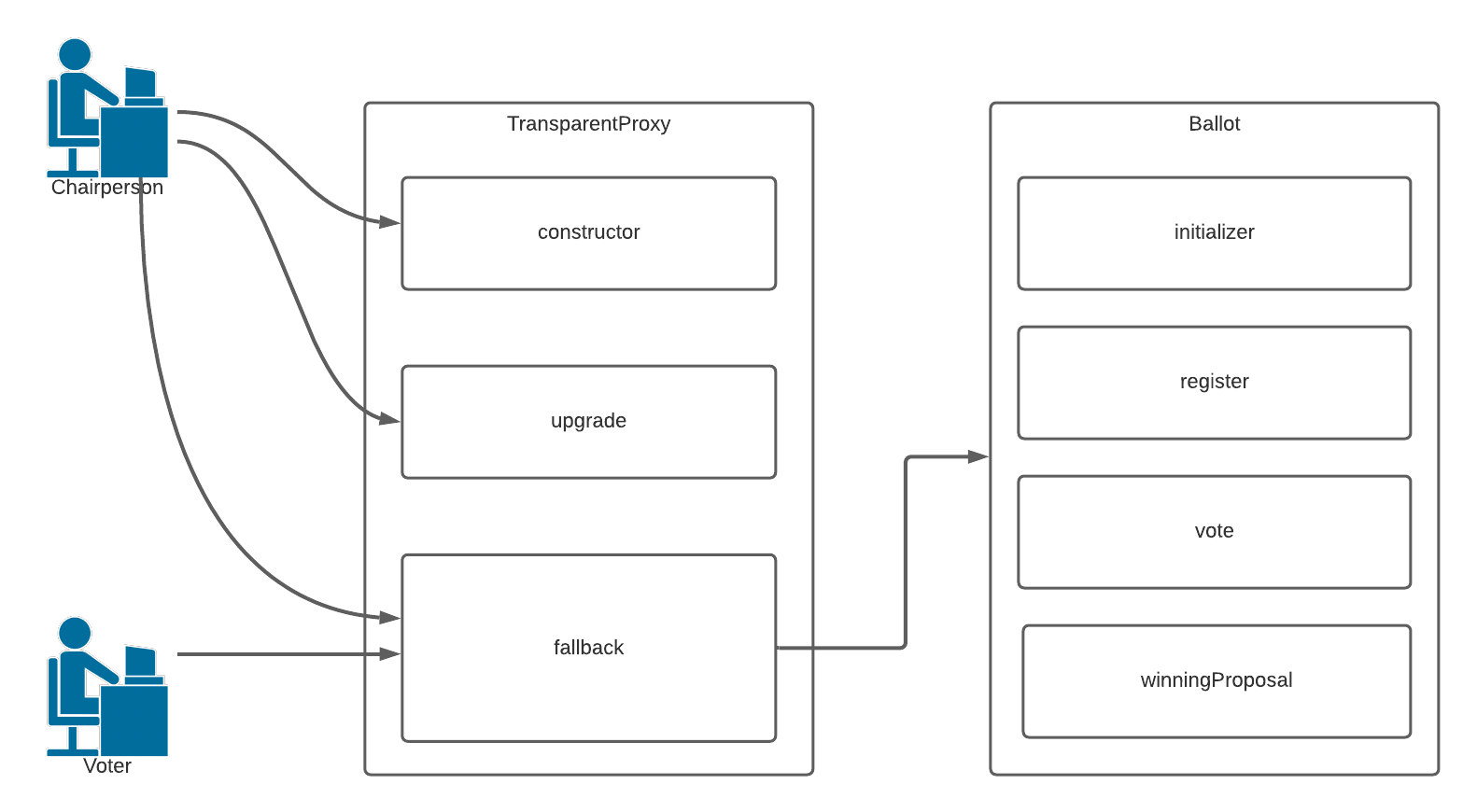

Now, our client interaction looks like this:

One final point worth noting is that you’d want to be sure to deploy the logic contract and call the ‘initialize’ function inside of a single transaction, to prevent someone racing you to become the chair-person.

Using this model, we can now upgrade the logic of our contract to use a duration of greater than 30 seconds in the event of a solar flare! It would be as simple as re-deploying the contract, minus the initialize function, with time constants that represent the new voting duration. We could even include a new initialize function to change the stage of the current contract, if needed.

And there you have it - upgradability on the immutable blockchain.

The whole thing can be found in a repo here, but I don’t recommend you use it for anything other than educational purposes.

Bonus track

The astute reader will have noticed an additional check in the initializer:

require(chairperson == address(0x0)); //prevent re-initialization

Initializers are not like constructors, they are written to the blockchain and can be called time and time again, which constructors cannot. It is important to prevent your contract being re-initialized by a malicious third party. This might sound obvious, but it’s happened.

ValueDefi was hit when their initializer function failed to record that it had been initialized. This one-line mistake cost ValueDefi 205,659.22 BUSD and 8790.77 BNB, a costly mistake indeed.