If you’re reading this blog, you’ve probably heard of flash-loan attacks. If not, here’s an example of one in action.

tldr; a flash loan allows a contract to make a totally uncollateralized loan as long as that loan is paid back with a fee in the same transaction - relaxing the rules on collateral enables flash loans to be truly massive. These massive loans are then use to manipulate prices which enable further economic exploitation.

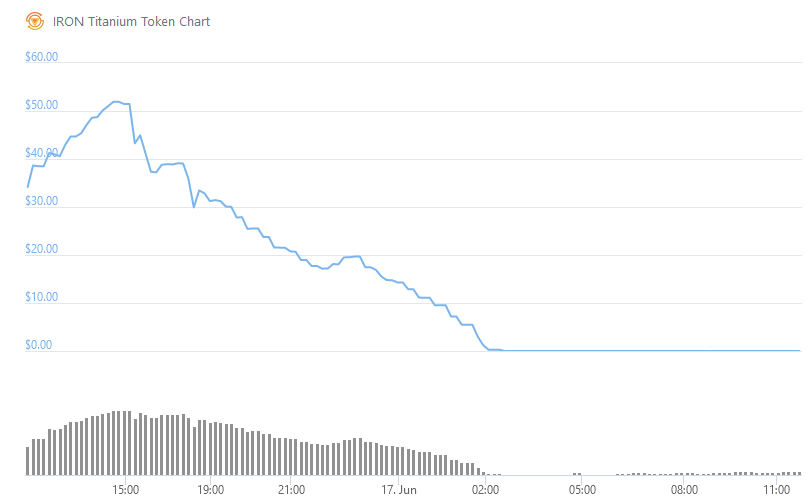

Iron-Finance was recently exploited by arbitrageurs in such a way that their TITAN token went to zero in a matter of hours. The exploit took advantage of a mitigation which was put in place to prevent flash-loan attacks, a Time-Weighted-Average-Price (TWAP) oracle. This design flaw made it possible for arbitrageurs to mint excessive amounts of TITAN, which they then dumped on the market.

In this post, I’m not going to discuss the low-level details of the IRON design-flaw, I hope to do that in a future post when the dust has settled and I’ve had the time to do a full assessment.

What is a TWAP Oracle?

One of the popular mitigations for protecting a contract against flash-loan attacks is to make pricing oracles more resilient against sudden changes in price which are made possible by flash-loans. One way of implementing such an oracle might be to record the price at a regular interval over a period of time, and then use the average price as your ground truth.

This is essentially TWAP pricing oracle.

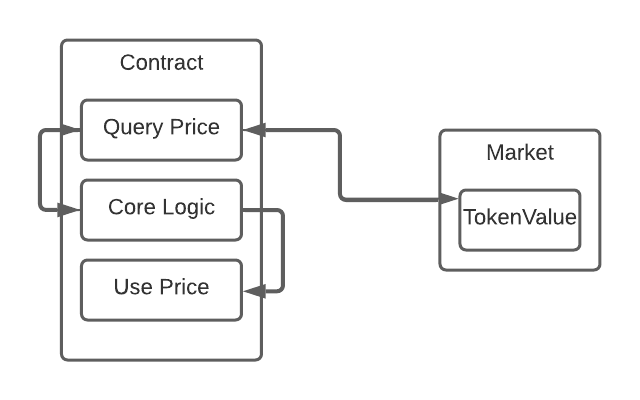

Consider the following architecture:

The contract in question needs to make business logic decisions based on the price of a token.

- How much LP do I mint?

- How much of token X can this LP be redeemed for?

- How much of token Y should I mint based on some input?

- How large should this reward or fee be?

- Etc…

So it queries a market (or multiple markets) to determine the going rate of some token.

The problem with this architecture is that a contract can trivially use a flash loan to manipulate TokenValue in the market in order to exploit the logic of the contract.

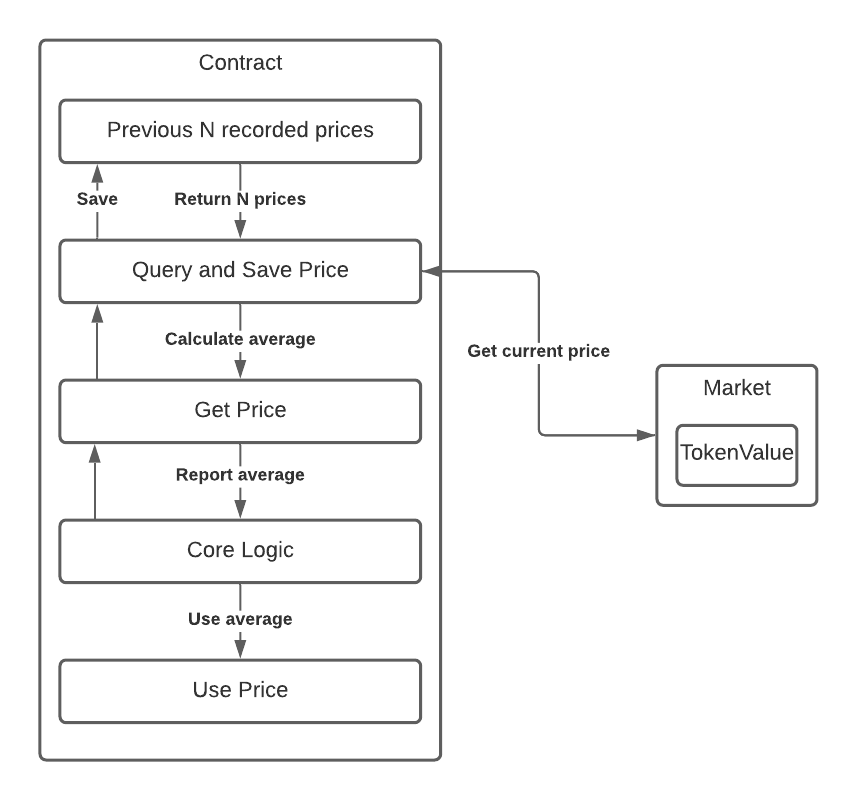

So how does a TWAP oracle help? Consider the following architecture:

Now our contract reaches into a record of some number of prices N, calculates the average price based on those recorded values.

It’s a neat idea. Now instead of the flash loan causing a big swing in the price, its effect might be lessened by taking into account many unaltered prices. You could even choose to ignore recorded price points which deviate from the norm by too much, to prevent a flash-loan from creating small arbitrage opportunities which might still render your contract vulnerable to an economic exploit.

All of this sounds great. Just like that, we’ve dramatically reduced the effectiveness of flash-loan attacks on our pricing oracle. But have we changed any of the other properties of our algorithm? As it turns out, the answer is yes.

Exploiting TWAPs

TWAPs prevent massive and sudden price swings from affecting the price reported by the oracle.

But what if there really has been a massive price-swing?

As anyone who’s been in DeFi for a little bit of time will tell you, massive price swings are the name of the game, and not just because of flash-loans.

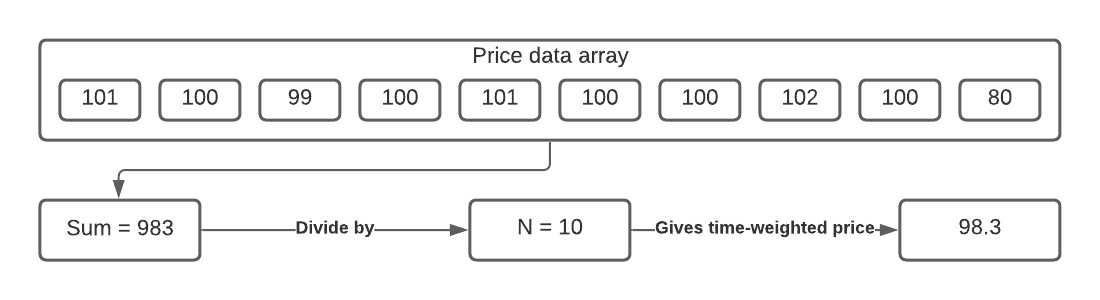

Lets imagine that there has been a massive price swing - the value of some token has been reduced by twenty percent over the space of a two or three blocks, and lets imagine our smart contract uses ten prices (N = 10), at a recording interval of five blocks. (The price values here are arbitrary units).

Going back to our previous example, the array which is being used to record the previous pricing data might look like the following (note this is a naive example of a TWAP, just to illustrate the concept. Real TWAPs are more complicated):

We now have what is fundamentally the exact same problem that our TWAP was here to solve - our pricing oracle’s price data is not representative of the real asset, but it’s misrepresenting it in a different way. Instead of being influenced by a flash-loan, the price really has changed, and there’s now a time-window where we have stale data in our price-point array which is going to cause our oracle to report an incorrect price until that stale data is cleared.

Depending on the business logic of our contract, that could be a really big deal.

In the case of IRON-Finance, it was.

It would appear that these circumstances led to a situation in which it was possible to redeem IRON for more than its market value in USDC and TITAN. That TITAN was then dumped on the market, driving the price down further. As the price plummeted more and more, the IRON-Finance TWAP oracle was never able to catch-up, and this cyclic opportunitiy for arbitrage existed for long enough to drive the price of TITAN to zero.

Conclusion

In computer-science, there’s very rarely a free lunch. Algorithmic changes which give you certain properties you want often give you other properties you hadn’t anticipated, which you didn’t want. This is an instance of just such a property. When the dust has settled, I’ll do a more thorough breakdown of the pieces of code which made all of this possible.

If anything, this is a reminder that the Ethereum developers can work hard to do everything right - include up-to-date best security practices, and still get burned.

Never invest more than you are willing to lose.